What’s inside the issue?

Click the links for a teaser excerpt of each piece…

Letter from the Editor

In a recent yoga class, the teacher told us about a lesser-known Hindu goddess. Her name is Akhilandeshwari. She hops on top of her fear, the alligator, and steers it down the river of life, breaking apart and recreating herself at all times. Her name translates in English to: She Who Is Never Not Broken.

When I search for this goddess online I don’t find much more than this little bit my yoga teacher shared, but one point is emphasized in everything I read: the double negative in her name. Instead of “always broken,” it’s “Never Not Broken,” emphasizing the brokenness. Each source repeats that her power comes from her brokenness.

I think about how counterintuitive it seems to consider something broken as powerful, especially in American culture where we usually associate brokenness with weakness. We are obsessed with the strength, vitality, speed, and beauty of youth, of athletes, of celebrities. We are obsessed with being the biggest, the strongest, the fastest, the best we can possibly be. These qualities get the spotlight and the glory, while the sick, wounded, weak, and broken sit on the sidelines and, sometimes, even hide in the shadows.

How can something broken be powerful?

By definition, if it’s broken, it has lost its power.

I have been feeling broken for a long time, in wake of the MS relapse I experienced at the end of August 2022. It has definitely left me feeling broken physically, but also emotionally and spiritually. It’s exhausting. It’s draining. To have so much of your focus consumed by illness and managing health can easily cause you to feel helpless and, worse, hopeless. It crushes your spirit.

And, yet, even when I was at my worst, I found ways to do what I was able to do and what I needed to do. I wasn’t (and still am not, in some ways) able to do things the way I used to. I wasn’t (and still am not, in some ways) able to do all of the things I used to do. But I still write weekly emails. I am still working on revamping my business to move forward in a way that does work for me. I still go to yoga, and do as much movement as I can, resting as much as I need to along the way. I still publish this magazine.

Then I realize: THAT is exactly the power and strength of brokenness.

It’s the power to feel as low as you’ve ever felt and still find it within yourself to exert the smallest amount of energy. It’s the power to acknowledge and embrace our own brokenness so that we can transform it into something useful and beautiful—like a story.

As soon as I heard about the goddess She Who Is Never Not Broken, immediately I thought of all the authors we have published, and continue to publish, in these pages. This issue is no different—with stories of our connection to place and how it shapes us, caring for and saying goodbye to loved ones at the end of their lives, wrestling with our own desires, and learning to love our own differences as the thing that makes us unlike anyone else in the world.

These are stories of what it means to be a human, a human who is never not broken.

Here’s to telling stories without shame,

Janna Marlies Maron

Editor & Publisher

Contributing Authors

-

Laura Julier

Laura Julier

Once I Owned a HouseOnce I owned a house. It was a small house in Iowa City, near Plum Grove, the home of Iowa’s first governor. It began as a corner grocery store in the early 1900s, but its overlarge back door was the only part that still looked like what it had been. Its interior walls were flimsy and its four rooms tiny. In the deep back yard was an old plum tree, an enormous pussywillow tree, a thicket of raspberry canes, lilac bushes, and a large walnut tree back near the alley.

Although I owned it for only eight years and those eight years are long ago, even now if I am quiet, I can hear its sounds—a dog barking behind the alley, a child’s voice, a father calling, the padded hush of thick gardens, the boards on the back deck and the brush of snow on the windows. These are the sounds embedded in my blood and my bones. When I close my eyes I can hear them no matter where I am. I do not have to tap my heels three times. I know the smell of earth under the raspberries, the shade of the buds on the lilac bush in the far back corner where I buried the divorce papers, can remember in my bones the rhythmic thuds when someone walks up the five steps to the front door. For years afterwards, my muscles and nerve pathways and internal clocks were all still finely attuned to that house, its sounds, its angles.

Although I owned it for only eight years, they may as well have been twenty-eight. In that house I lived alone with my first cat, Penelope. I learned to till a garden, to turn in compost, learned that blood meal will repel rabbits, that tomatoes can’t grow too close to black walnut trees. I learned to transplant things—it began with chrysanthemums and iris—to find and kill squash bugs by hand, to save seeds and start them early. That garter snakes hang in raspberry canes and that fledgling cardinals leave their nests before they can fly. I learned to can vegetables and to make jam from the fruit of the mulberry tree by the front curb.

Laura Julier is a writer whose lyric memoir, Off Izaak Walton Road, won the 2023 River Teeth Literary Nonfiction Book Prize and is forthcoming from University of New Mexico Press in 2025. This essay is from that book. She was editor of Fourth Genre for nine years. She currently lives, once again, in a house she loves in Iowa City.

-

C. Meaker

C. Meaker

LateLet’s start at the point of departure, the jump-off—whose roots are perhaps tied to indigent travelers hopping from boxcars, or paratroopers launching from a plane, or perhaps someone choosing to dive from a cliff into an unknown depth for the thrill—activities impossible for the anxiety they produce, but perhaps desirable for their efficiency. One would be sure to arrive on time by those routes, though bruised. My father insisted on arriving to the airport three hours before departure. He would alter our plans without notice, sitting in the van with the engine running thirty minutes earlier than agreed upon, ready. I’d haul ass, lest I be left behind. My mother making sure lights were off, shoes tied, doors locked, incanted—

He can wait he can wait

—and he did, though he stressed about arrivals, about traffic, about the unforeseen causing delays, white-knuckling the steering wheel, ruining the novelty of shifting loci for everyone in the backseat. He would never acknowledge that he had changed the plan, bumped our departure forward, insisting he’d always meant to leave at the earlier time.

C. “Meaks” Meaker is a playwright and essayist whose work explores queerness, monstrosity, and the end of the world. Their plays have been developed at the Kennedy Center, Seattle Repertory Theatre, San Francisco Playhouse, Annex Theatre in Seattle, and About Face in Chicago. They received an MFA from University of Iowa’s Playwrights Workshop. Awards: Jerome Fellow at the Playwrights’ Center; Walter E. Dakin Fellow at Sewanee Writers’ Conference; Editor’s Prize in Nonfiction at Porter House Review.

-

Mauri Pollard Johnson

Mauri Pollard Johnson

How to Know If You Are NestingWhen you tell your hairstylist that your mother is readying her house for your twenty-one-year-old younger sister to return home after living a year abroad in France by organizing buckets of Legos from the back shelves of closets, hoisting herself into the attic to find puzzles with missing pieces and clean off dusty Christmas books, washing dozens of American Girl doll outfits, and intricately styling each doll’s hair, your hairstylist says, “Oh my gosh, she’s totally nesting,” and you realize she’s right. And you think of how pregnant women are often drawn to painting, organizing, deep cleaning, rearranging, remodeling, and repairing their homes before giving birth. And you realize it has been fourteen years since your mother was last pregnant, but this instinct has never left her.

And this makes you consider the ways that you might be nesting too, because although you have no children, aren’t pregnant, don’t want to be pregnant, and may never want to be pregnant, you are a woman, and you’ve been married for almost five years, and people have been asking for at least the past three years, “When are you going to have a baby?” because most women in your Christian community get pregnant so quickly into their marriages that for some reason people seem to think they have the right to know when you will start popping out babies because you are a woman and this is what women do. They have babies.

Mauri Pollard Johnson is an essayist, writing teacher, and amateur poet. She earned her MFA degree in Utah where she lives with her husband and their spunky calico cat. Just as much as she values writing, reading, and analyzing literary pieces, she also values and enjoys watching reality dating shows, reading Hockey Romances, and listening to Taylor Swift. Her work has appeared in The Normal School, Inscape Journal, Punctuate, Dialogue, and others.

-

Allison Kirkland

Allison Kirkland

Loving the AlienI sneezed and dust flew out of the towering oak console that housed my dad’s massive record collection, where I was sifting through the heavy cardboard and plastic discs. In between homework and my middle school classes I spent lots of time poring through sixties and seventies rock music with my dad. He had a way of choosing the perfect song for whatever I was feeling that day. Today he picked David Bowie’s self-titled album, that begins with the song “Space Oddity.” As he helped me maneuver the large disc safely onto the turntable, which he always did because they were unwieldy in my unusual hands, he smiled and said, “You’re in for a treat.”

The round pieces of plastic were always so flat until I dropped the needle and they bloomed into sound that took up physical space, crawling around the room. A whole world lived in that flat space. When I dropped the needle this time, ground control counted down and I was lifted out of my living room, rocketed through each layer of the atmosphere and into space. “Space Oddity” turned the spinning world on its axis, lit the stars brighter against the night sky, made me feel that songs I’d heard before might have been fun and entertaining but that they didn’t really matter that much.

Allison Kirkland holds an MFA in creative nonfiction from The New School and leads creative writing workshops online and in Durham, North Carolina. Her publications include personal essays, interviews and arts journalism, and her work has received support from the North Carolina Arts Council and the Durham Arts Council. She is currently working on a memoir. You can subscribe to her Substack, the intangibles, at allisonkirkland.substack.com.

-

Katie Rose Rogers

Katie Rose Rogers

I Imagine You Will Read This SomedayLast night, a ghost called my name and because I intend for this not to be fiction, I will tell you what he said. He said, “Katie.”

I don’t want to debate whether it was night or morning, so I will give you the exact time. 2:12 a.m. PST. In my work, I rarely get an exact time. It’s either—

INT. HALLWAY – LATE NIGHT

OR

INT. HALLWAY – EARLY MORNING

It’s comforting to be able to say something as definite as 2:12 a.m. and know I will not discuss or debate what that means in terms of darkness or light, my levels of exhaustion, or what that means for the character (me) that I am awake at this time. I can tell you simply, for we are dealing in truths, that I know the time for a reason. I was awake. An earthquake had struck off the coast of Malibu and slowly crawled its way to Pasadena.

The next morning over coffee, I told my husband (your dad) that I woke with a start—whole moments before the rolling and shaking, but he believes my mind gave me a moment of kindness. A moment of stillness before the old walls of our one-hundred year old Spanish bungalow (which proudly survived Northridge) shifted in their dirt. But regardless, whether he or I am right, whether I have a kind mind, or an anticipating one— my eyes opened. I watched the light fixture above my head sway. I cradled my belly and counted down from five. You kicked.

Thank you for kicking.

Katie Rose Rogers is a writer born and raised in Southern California. Her words live in fiction, poetry, and television. You can find her television writing on CW’s Supergirl or Showtime and Paramount+ Fellow Travelers. Or listen to some of her scifi short stories on the podcast Unlikeminded. Currently residing in rose-worn Pasadena, she is busy helping her sourdough starter, her child, and her husband thrive while sharpening her writer’s edge.

-

Aaron Gilbreath

Aaron Gilbreath

Becoming An OregonianOne September morning I woke up and realized I’d treated the dry east side of my state unfairly.

Since moving to Oregon twenty-three years ago, I’ve hiked, camped, and driven around what Northwesterners call “the high desert” and the arid Columbia Plateau many times. I grew up in Phoenix, Arizona. I love desert plants, desert critters, and the views deserts’ openness affords. When I left Arizona at twenty-five, I told myself that if there was a desert in my adopted home, I wanted to see it. But the Sonoran Desert where I grew up is the lushest desert in the world. It was hot and dry but very green. Diverse cacti and shrubs supported impressive reptile, mammal, and insect diversity. It had plants that grew tall enough to qualify as trees, like the native ironwood tree and the green-skinned Palo Verde. The iconic saguaro cactuses seem arboreal, having branch-like candelabra shapes and shadows that help other plants sprout in their shade. You can step outside on any night and find coyotes, bats, and insects. Ecologically and aesthetically, my desert set a high bar for other deserts to live up to. So when I explored eastern Oregon and eastern Washington, all I perceived was a brown monoscape.

The massive Cascade Mountains divide Oregon and Washington in half. Those towering mountains capture moisture blowing in from the Pacific, creating a rain shadow effect that alters the weather so severely that they create a wet, green, forested west side and a dry, hot, scrubby east side. The more time I spent on the east side, the more it disappointed me.

Aaron Gilbreath is a writer whose essays and reporting have appeared in Harper’s, The Atlantic, Adventure Journal, Sierra, Kenyon Review, High Country News, The Dublin Review, and been named notable in Best American Essays, Best American Travel Writing, and Best American Sports Writing. His third book, The Heart of California: Exploring the San Joaquin Valley, was a finalist for the 2022 Oregon Book Award. He runs the Alive in the Nineties music series on Substack, likes to skate and make collages.

Contributing Artists

-

Landforms, Julieanne Kost

Julieanne Kost

LandformsJulieanne Kost is a photographer and artist whose work combines her passion for photography, mastery of digital imaging techniques and her degree in psychology into surreal and inventive works that present physical landscapes as mysterious worlds. Her work has been exhibited numerous times and featured in several publications including NatGeo Traveler, CNN Travel, Behance.net, FUBIZ, PetaPixel.com, thisiscolossal.com, CreateMagazine, and Australian Photography Magazine. Kost holds an AA in Fine Art Photography and a BS in Psychology. jkost.net/photography

@jkost

-

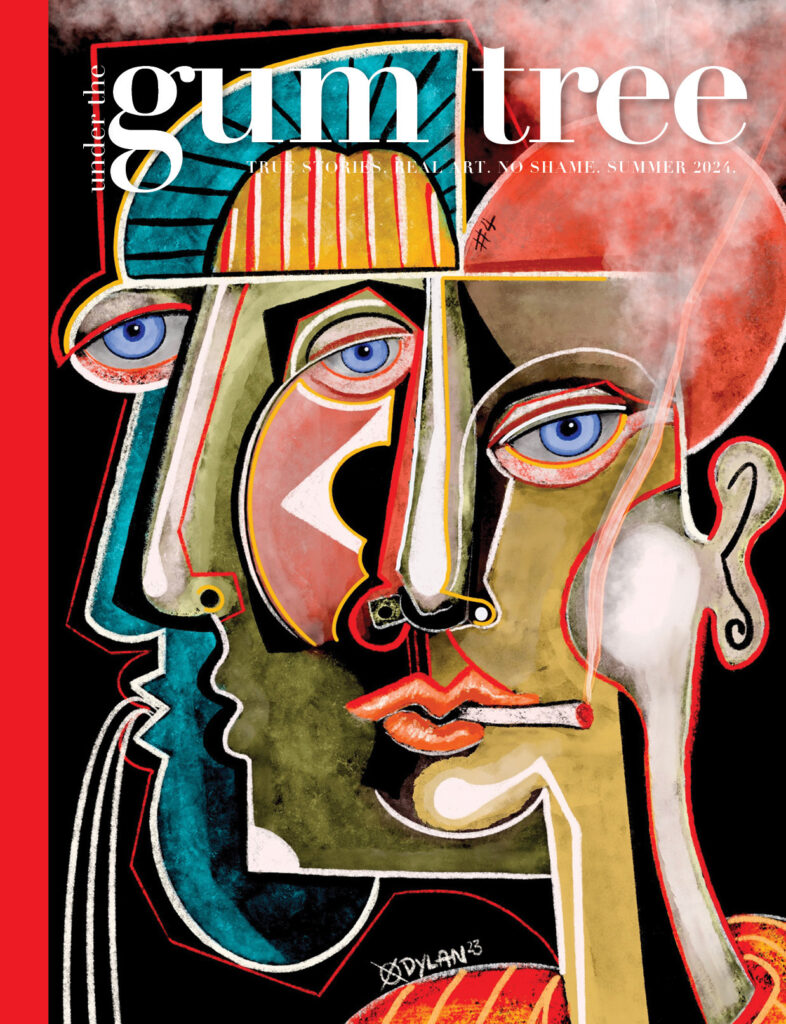

Endeavour, Dylan Gill

Dylan Gill

EndeavourDylan Gill is an artist based in London whose work explores the relationship between shape and color. He studied fine art at the Goldsmiths, University of London and has exhibited across Europe, including London and Paris and in Asia, including Singapore and Vietnam. dylangillart.org

@popartdyl