Sara Dobie Bauer

Sara Dobie Bauer is a writer and prison volunteer in Pheonix, Arizona, with an honor’s degree in creative writing from Ohio University. She is a book nerd and sex-pert at SheKnows.com, and her short fiction has appeared in The Molotov Cocktail, Stoneslide Corrective, Blank Fiction, and Solarcide. Her short story, “Don’t Ball the Boss,” was nominated for the 2015 Pushcart prize. You can read more about Sara at her blog here.

Sara’s piece, “You Were Here,” is her visceral and emotional retelling of how a place, such as a family home that you’ve grown up in and visited for thirty-some-odd years, ultimately shapes the person you become. Sara’s piece is also an exploration of both the haunting question of how memories and people, whether long or recently departed, continue to stay with us, and how feelings are individually linked to the memories we have and to the people of whom we have them.

Down below, you can see four pictures taken of Sara’s family and her childhood home which encompass the heart behind her wanting to write this piece.

This story is incredibly warm, but also tinged with feelings of emptiness; wishing you’d done more with the time you had. Was the intent of this story to process the emotions centered around your Papa’s death, and to accept the idea that things change, or was it an attempt to salvage some of the memories that were becoming clouded over time?

Truth? I flew home to Perrysburg under emotional duress, knowing we would soon sell my grandparents’ house. I arrived at the house on Walnut Street. I asked to be left alone, and I opened a beer. Then, I carried my computer from room to room and just … wrote. And cried. Lots of crying. I wrote this entire essay in one sitting with the help of three beers and a box of tissues.

The intent was selfish. I did want to remember things (record them for posterity), but I wrote the essay to help me process the horrible ache in my heart at the thought of never again setting foot in my grandparents’ home. When the essay was finished, I showed it to one person who cried and cried over it. When I told her it was being published, she was shocked I’d even sent it out for consideration. She thought it was too personal.

Once others who have been so monumental in our lives have passed, it’s hard to accept the idea that we can’t tell them a joke we liked—that they would have liked too, or a song we want them to hear. It’s hard to not pick up the phone and feel that it’s still possible to call them. Do you feel like this story and writing in general, have helped you to find peace with these feelings that arise?

Writing is a form of exorcism. Many of my stories are recycled nightmares that won’t leave me alone, that would fester if left inside my brain and not set free on an unsuspecting populace.

Peace sounds very nice in the Biblical sense and in beauty pageants. In life, peace feels like a glassy pool, left to stagnate. We live with adversity. If we didn’t have a force pushing against us, we wouldn’t push back. In the pushing, we find our strength.

When you were experiencing the apex of these emotions, was there anyone who truly understood what you felt? Your brother, who was present in all of the memories you recounted us, perhaps?

Feelings are individualized entities. Do I feel like my family could relate to this piece? Of course. Did anyone TRULY understand? I’m not sure. A writer’s mind is a strange place. Our imaginations are so visceral. For me, I can pull up a memory from ten years ago and feel like I’m there (a blessing and curse; more often, curse).

What’s interesting about my brother is that he’s a writer, too, but we operate with different intent. Matt keeps a distance from his creation. He can be very satirical and dark, but he rarely brings his own life into the mix. I think the way I open my heart for scrutiny scares him a little. Could he have written and shared “You Were Here”? No, but that doesn’t mean he didn’t feel it.

The theme of change is prevalent in your story. Many of the characters appear to evolve, but the traditions of the family remain untouched—even the detail of the thirty-year-olds sitting on the floor, despite the fact that they’re adults. Why do you think we tend to hold on to our traditions so tightly?

No matter what happened, there was always the tradition of Christmas for my family. On December 24th, we knew exactly where we were going to be and what we were going to be doing. There was comfort in that repetition—in the knowledge that even if the rest of the world is turning cattywumpus, Christmas waits. The same goes for any tradition. Traditions ground us and define our identities, even subconsciously. When those traditions are gone, we lose a part of ourselves. This is why we hold on so tightly; it’s horrible when we feel a part of ourselves die.

Do you believe the line between memories and reality is blurred in this story, or do you think you portrayed the events as they actually happened? If all the family members in this piece were to read this, would they feel it was an accurate representation?

This story is my reality, and memories form that reality. To me, these are the events as they actually happened. For the rest of my family, probably not. We all see life through our own rose-tinted glasses (or blue-tinted, yellow-tinted … you get the idea). I imagine some of my family members might be annoyed by the way I see “us.”

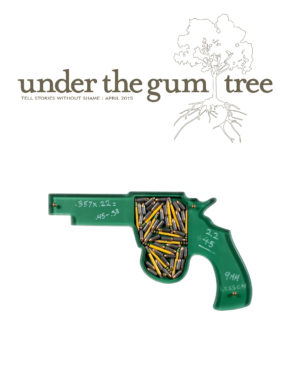

In my mom’s case, I sent her the printed version of the story in Under the Gum Tree. She initially planned to skim the first paragraph. Twenty minutes later, she’d read the whole thing and called to thank me—thank me for putting our family on the page. That’s what “You Were Here” is: a retelling so that when my own memories start to fade, I will have a story to look back on. A time machine to remembrance.

Do you find there is a difference between memories and ghosts?

They both have the power to haunt us but, in equal turn, bring us joy. Memories exist like shadows in the corner of the room. We know the memories are there, but if we turn too fast, we scare them away. Also, if we spend too much time with those memories, we become ghosts. We forget to live.

When you write that you “believe the past is alive,” how are we to interpret this? Are we to believe that the past is an electric collection of these memories preserved in physical retainers, such as the rooms in your grandparents’ house, and in their possessions, even in our own bodies and minds? Or could it be that regardless of our efforts to keep the past alive, it will still pervade our lives in ways that we can’t control?

The past is alive because it lives on through us, via stories, traditions, and even dreams. For instance, I often dream of the house on Walnut Street. In those dreams, my family is alive and together. They will never die. It’s like the saying, “What we do now echoes in eternity.” The past was once the present, so live the present in a way that will make the past a happy, meaningful place to recall.

Do you have anything else to share about this piece that hasn’t yet been touched upon? Did you have a favorite room or favorite particular memory in the house?

Favorite room: The basement. Why? The Ping-Pong table. We left it behind when we sold the house in the hopes that it would find players again—in the hopes that children’s laughter will again echo beside the ricochet of a plastic ball bouncing, bouncing.

My favorite memory is and always will be one of the final Christmases we had together before Barney died. I bought Papa his first bottle of expensive gin. He played swing music on a record player in the kitchen. We all danced—all of us. We all laughed and got along. No one was sick or dying or sad. Looking back, this might have been the last time we were all together as a family. The last Christmas before Christmas changed forever. Is that why it’s my favorite memory—simply because it was our last as a collective? Or is this my favorite memory because we were all, unabashedly, happy to be alive, together, in the house on Walnut Street?